Translate this page into:

Leiomyosarcoma of Uterus in a Nulliparous Female: Mimicking as Ovarian Malignancy

Address for correspondence Jagannath Mishra, MCh, Department of Gynecological Oncology, Acharya Harihar Regional Cancer Center, Cuttack, Odisha 753007, India. jagannathmishra05@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Uterine sarcoma is a rare verity of smooth muscle tumor, accounting for 2 to 6% of uterine malignancies. Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) represents ∼1% of overall uterine tumors and ∼25 to 36% of uterine sarcomas. Here we present a case of uterine LMS in a 34-year-old nulliparous woman presented with huge distension of abdomen which was confused to be an ovarian malignancy. She underwent total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The diagnosis of LMS is made by histopathological examination after surgery. Surgery is the only treatment and role of adjuvant therapy has not been clearly defined.

Keywords

leiomyosarcoma

nulliparous

uterine sarcoma

Introduction

Uterine sarcoma has three most common variants which include endometrial stromal sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma (LMS), and carcinosarcoma.1 Carcinosarcomas have both epithelial and mesenchymal components and are now thought to be metaplastic carcinomas, rather than a subgroup of sarcomas.2 LMSs are the most common variety, which represents ∼25 to 36% of uterine sarcomas.3 It is generally seen in younger individuals (age 43–53 years).4 Stage is considered to be the most important prognostic factor of LMS and rarity of this tumor is the main cause for our lack of knowledge in other prognostic factors and adjuvant treatment.

Case Report

A 34-year-old nulliparous woman came to our outpatient department (OPD) with complaints of abdominal distension for the last 3 months. She was evaluated for this complaint at her local hospital as a case of ovarian malignancy with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) abdomen and pelvis, and other tumor makers of ovarian tumor. The CECT finding was that of a heterogeneous hypoechoic abdominopelvic lesion with cystic areas within and contrast enhancement located posterior to urinary bladder extending up to supraumbilical region possibly malignant ovarian tumor involving uterus (Fig. 1). The mass was found to be adhered to abdominal wall, large bowel, and omentum. Bilateral ovaries were not separately imaged. There was minimal free fluid in the peritoneal cavity and there was no evidence of retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Her CA-125 was 422 µ/mL. Rest of the markers including ovarian germ cell markers (even lactate dehydrogenase [LDH]) were within normal limits. She also underwent laparotomy outside but due to dense adhesion of bowel to surface of tumor only biopsy was done, which suggested it is a case of symplastic leiomyoma.

-

Fig. 1 CECT scan showing huge abdominopelvic mass which is hetrogenous with omental adhesions CECT, contrast-enhanced computed tomography.

With this report we examined her.

She was thinly built with a body mass index (BMI) of 14.3 and her ECOG (eastern cooperative oncology group) was 0. Mild pallor was present. Her vitals were stable with pulse rate of 70/min, blood pressure 126/80 mm Hg, and respiratory rate 22/min; on abdominal examination, a firm midline mass was palpable, which was ∼28 weeks’ size of a pregnant uterus and had irregular surface. The mass was not mobile. On speculum and bimanual examination, the cervix was nulliparous, directed backward; same mass was felt in anterior and bilateral fornices and no tenderness was observed. As the mass was big in this thin lady and all the fornices were full, we were unable to arrive at an impression of a uterine mass.

Operative Findings

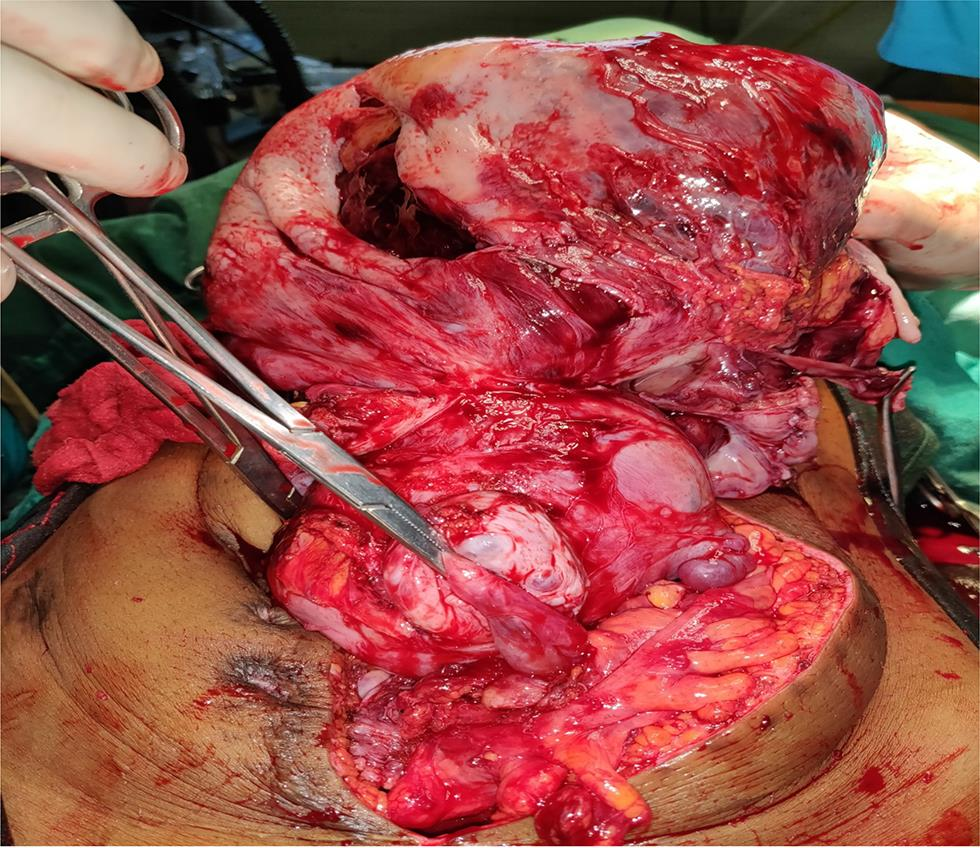

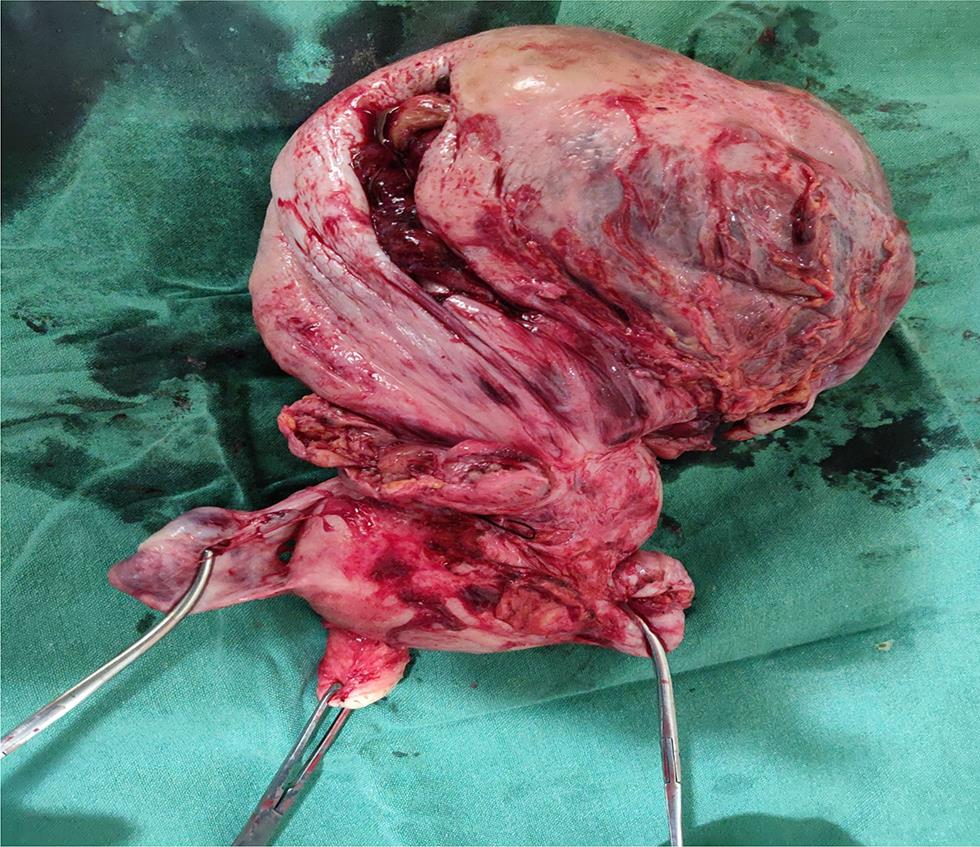

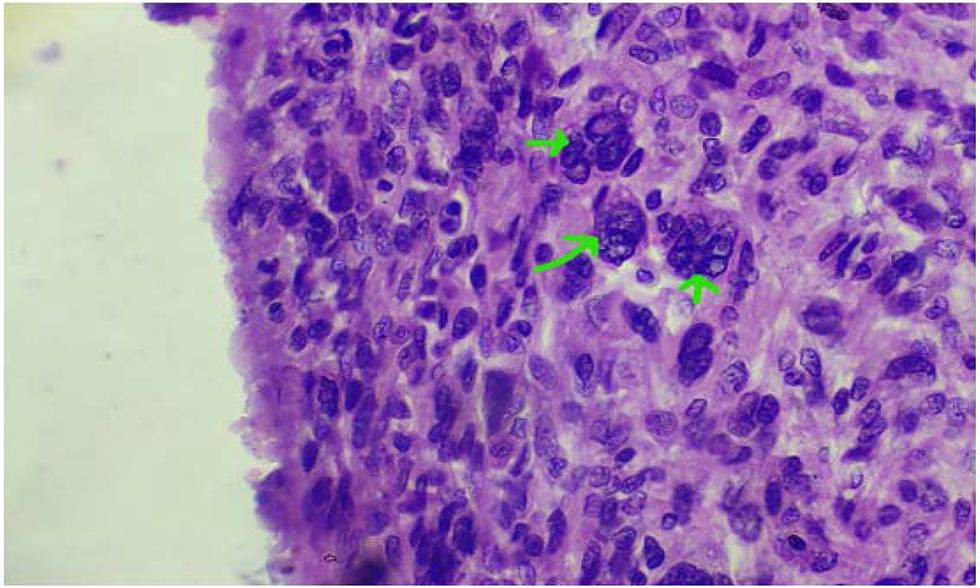

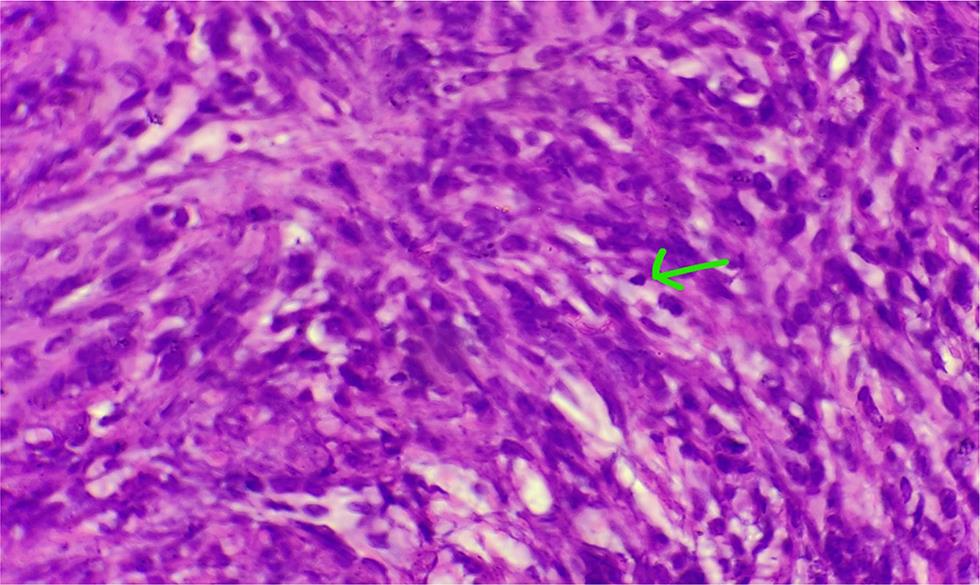

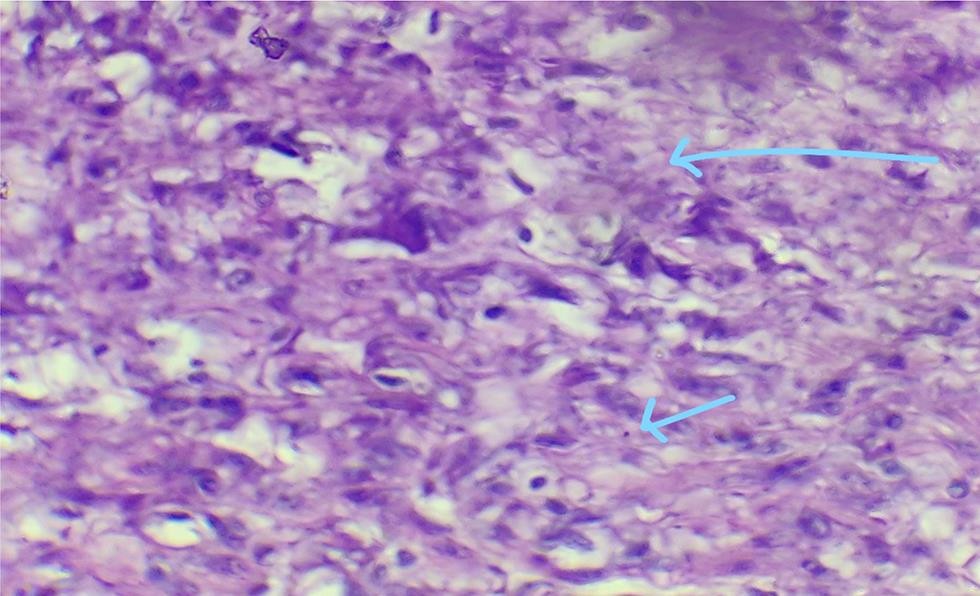

The surgery was performed under general anesthesia through a vertical incision intraoperatively; sigmoid colon and omentum were densely adhered to the mass. The mass was of 28 weeks’ size arising from the fundus of the uterus which was twisted with necrotic areas within (Figs. 2 and 3). Both ovaries were bulky. Gentle adhesiolysis was done to separate bowel and omentum, followed by total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy along with the mass. The whole mass along with uterus measured 37 cm and weighed 7.6 kg. Lymph nodes and other visceral organs were normal. The histopathology report (Figs. 45–6) showed interlacing bundles of spindle cells with elongated hyperchromatic nuclei. There were bizarre nuclei with multinucleate tumor giant cells and mitotic count was 6 to 7/high power field (HPF) with areas of necrosis which is one of the hallmarks of LMS. She was discharged on the 7th postoperative day. She was not offered any further adjuvant treatment as omental biopsy couldn’t show any metastatic deposits. She is disease free at the time of writing the manuscript. Her disease-free survival (DFS) is 6 months when the study was reported.

-

Fig. 2 (Intraoperative) Uterus with mass from fundus with B/L ovaries with sigmoid colon lie anteriorly and omental adhesion after adhesiolysis.

-

Fig. 3 Specimen showing leiomyosarcoma mass getting twisted from fundus with necrotic areas and B/L adnexa.

-

Fig. 4 Hyperchromatic and giant nucleus.

-

Fig. 5 Mitotic figure.

-

Fig. 6 Areas of necrosis (hallmark of leiomyosarcoma).

Discussion

LMS which arises de novo has multiple risk factors, like the patient being nulliparous, which was our case; history of pelvic radiation; as well as exposure to tamoxifen.5 Unfortunately, there are no specific symptoms that can differentiate it from leiomyoma which has definitely higher incidence in these young women.6 Our patient presented only with abdominal distension and the size of the mass was 28 weeks with irregular surface which one may think of LMS. At present, the lack of ability of imaging techniques to detect LMS, especially in differentiating it from leiomyoma, is disappointing. Rather, the imaging may be confused with ovarian mass as in our case. As the diagnosis of LMS is rare, additional diagnostic techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), PET-CT, and endometrial biopsy are not commonly used in clinical routine. But the age of patient was more in favor of LMS than ovarian malignancy. Serum LDH is often raised in LMS which may differentiate from leiomyoma but may be confused with ovarian dysgerminoma which is often seen in younger population. The diagnosis is confirmed only after surgery by histopathological examination and most cases are diagnosed incidentally after hysterectomy.7 Kohler et al8,9 have analyzed anamnestic and clinical criteria of 227 LMS and 3,920 leiomyoma and found the following discriminating items:

-

Postmenopausal status and/or postmenopausal bleeding.

-

Abnormal premenopausal bleeding.

-

Suspicious sonographic findings.

-

Rapid tumor growth and age > 45 years.

-

Tumor size > 8 cm.

The main treatment of LMS is surgical excision which consists of total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and debulking of any tumor invading outside the uterus. Ovaries can be preserved in young women and since lymph node involvement is seen in less than 3% of patients which is unlikely in the absence of extra uterine disease,10 lymphadenectomy is not advised in LMS unless it is enlarged. There is no role of fertility preserving surgery as the disease is highly aggressive and there is no evidence in literature owing to rarity of these tumors. Those nulliparous patients diagnosed after presumed leiomyoma desirous of pregnancy can be counseled about the risk of not undergoing debulking surgery and risk of recurrence. In those cases it would be beneficial to rule out metastasis by chest computed tomography (CT) and abdominopelvic CT/MRI. Once the reproductive function has been completed demolitive procedure should be considered. In general, adjuvant systemic therapy is not indicated outside of clinical studies. Data for systemic palliative treatment of advanced and recurrent tumors offer at least some possibilities, among them chemotherapy with docetaxel and gemcitabine. Adjuvant pelvic radiation with 50.4 Gy provided better local control in a randomized setting of stage I and II uterine sarcoma11; but the LMS subgroup (n = 99) did not profit with regard to local relapse rate (20% with and 24% without radiation) nor when overall survival is concerned. The average 5-year overall survival ranges from 62 to 65% in stage I disease, in contrast of advanced disease where the 5-year overall survival rate is as low as 29%.12 In a review of 208 women with LMS, Giuntoli et al13 devised a risk assessment index using the variables of age and tumor size, stage, and grade. Women were assigned points for each of these three variables: age >51 years; tumor size >5 cm; and stage II, III, or IV. In addition, 2 points were assigned for grade 2, 3, or 4. The women were then classified as low risk (0–1 points), intermediate risk (2–3 points), and high risk (4–5 points). This index proved to be highly predictive of disease-specific survival.

Conclusion

LMSs are highly aggressive tumors with poor prognosis. Imaging cannot identify patients with LMS, as it is difficult to differentiate from leiomyoma and sometimes from ovarian malignancy (like our case in advanced stages). Surgery is the mainstay modality of treatment. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy has not been proved due to the rarity of this tumor.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Uterine leiomyosarcomas: a review of the diagnostic and therapeutic pitfalls. Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;9:88-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- The treatment of uterine leiomyosarcoma. Results from a 10-year experience (1990-1999) at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92(02):648-652.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of uterine sarcoma after tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer: report of four cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15(06):1239-1242.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uterine sarcoma: twenty-seven years of experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57(05):1366-1373.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preoperative diagnosis and treatment results in 106 patients with uterine sarcoma in Hokkaido, Japan. Oncology. 2004;67(01):33-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kohler G, Belau A, Krichbaum J, et al. Deutsches klinisches Kompetenzzentrum für genitale Sarkome und Mischtumoren an der Universitätsmedizin Greifswald (DKMS) und Kooperationspartner VAAO Deutschland und FK Frankfurt/Sachsenhausen. Datenbank und Promotionsgruppe genitale Sarkome Greifswald 2015

- 2016. et al. Smooth Muscle and Stromal Tumors. Sarcoma of the Female Genitalia. Vol 1. Berlin, Germany: de Gruyter

- European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gynaecological Cancer Group. Phase III randomised study to evaluate the role of adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy in the treatment of uterine sarcomas stages I and II: an European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gynaecological Cancer Group Study (protocol 55874) Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(06):808-818.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and pathologic prognostic features of leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. Tumori. 1983;69(01):75-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Retrospective review of 208 patients with leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: prognostic indicators, surgical management, and adjuvant therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89(03):460-469.

- [Google Scholar]