Translate this page into:

Metastatic Extraskeletal Mesenchymal Chondrosarcoma of the Pancreas: Report of an Unusual Case with Review of Literature

Address for correspondence Saloni Naresh Shah, MD, Department of Histopathology and Cytology, Apollo Hospitals, Mezzanine Floor, 21, Greams Lane, off Greams Road, Chennai 600006, Tamil Nadu, India. saloni.1008@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma (ESMC) metastasizing to the pancreas in isolation is a rare occurrence. We report a 49-year-old gentleman who had undergone excision of an ESMC of the thigh in 2009 and presented with sudden onset abdominal pain and icterus in 2019. Radiological imaging revealed calcified mass of the pancreas with multiple nodules with extension into the adipose tissue. Distal pancreatectomy was performed and the pathology revealed a bimorphic tumor composed of undifferentiated round blue cells with abrupt transition to hyaline cartilage, typical of mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. To the best of our knowledge, there are only seven prior cases of metastatic ESMC of the pancreas in the English literature. Surgical intervention appears to be the preferred modality of treatment for metastatic pancreatic tumors. These patients may have long latency period before metastasizing and seem to have a good survival period post excision.

Keywords

extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma

metastasis

pancreas

Introduction

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma is a rare aggressive variant of chondrosarcoma, first described by Lightenstein and Bernstein in 1959.1 It accounts for less than 3% of chondrosarcomas. Extraskeletal occurrence, first described by Dowling in 1964,2 is seen in one-fifth to one-third of the cases. The commonest sites of involvement of extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma (ESMC) are the soft tissues of the orbit, meninges, and lower limbs. Visceral organ involvement is uncommon with few sporadic cases described in the thorax, abdomen, and retroperitoneum.3 Histologically, the tumor has a bimorphic morphology composed of undifferentiated round blue cells with abrupt transition to hyaline cartilage. Primary pancreatic mesenchymal chondrosarcomas are rare with only two reported cases.4,5 Also, only seven cases of metastatic ESMC of pancreas are described in the English literature,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 prompting this report.

Case Report

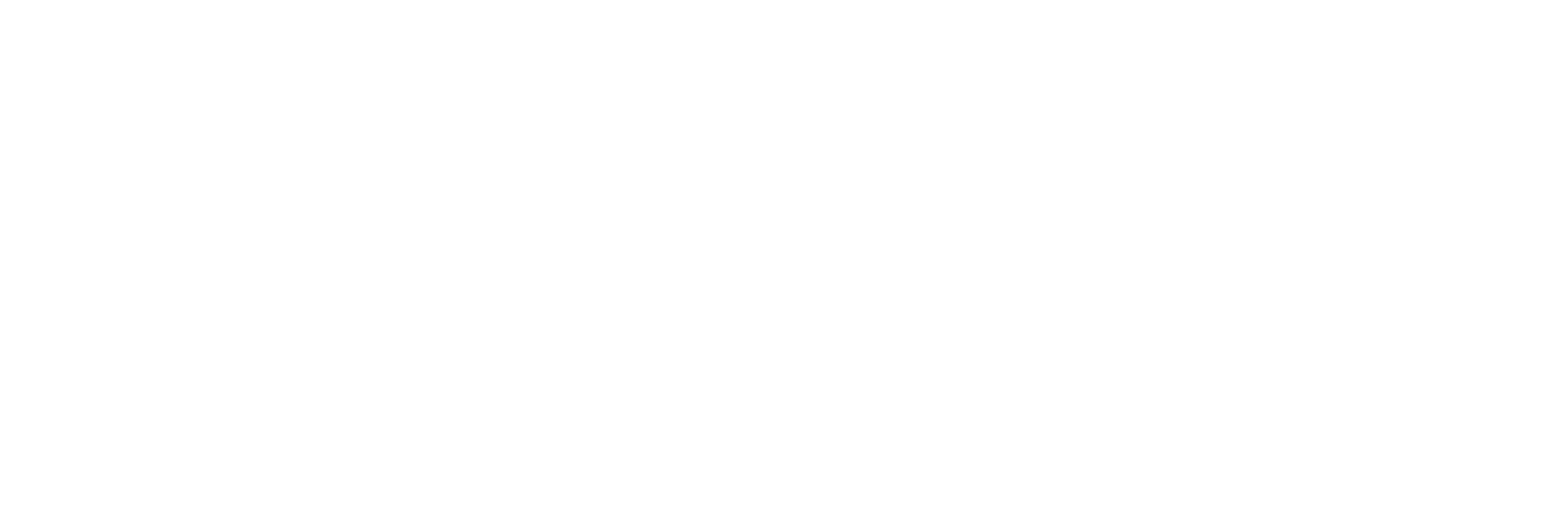

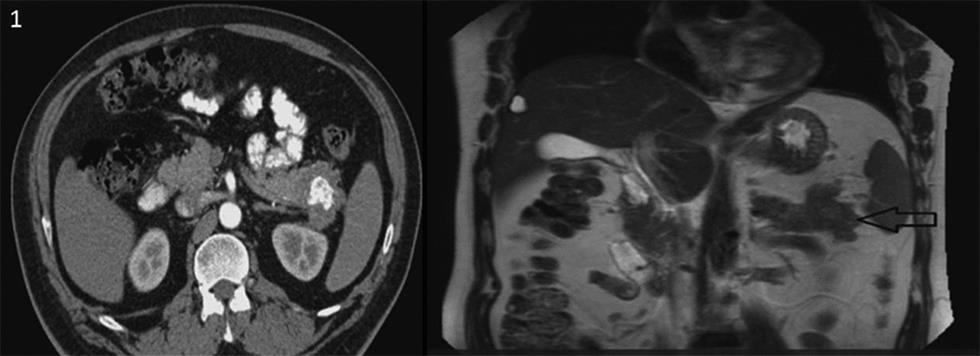

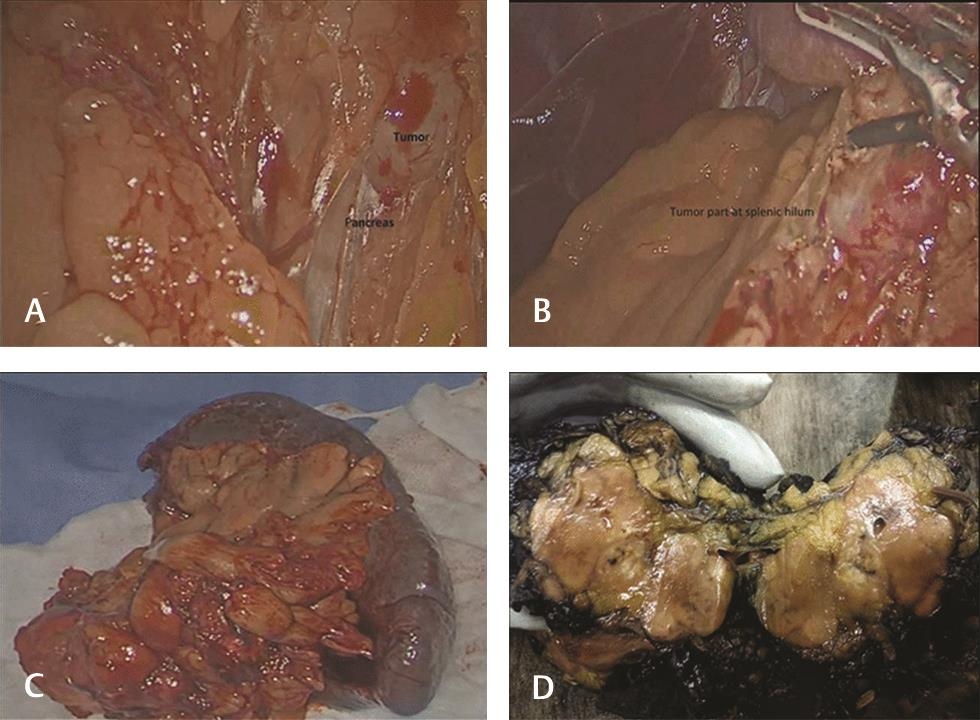

A 49-year-old gentleman presented in June 2018 with complaints of jaundice and abdominal discomfort of 1 month duration. On evaluation, computed tomography revealed an exophytic mass in the tail of pancreas abutting the splenic hilum and Gerota’s fascia (Fig. 1). The patient had a significant past history of ESMC of the right thigh in 2009 involving the soft tissue. Following a wide excision, he received chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In view of this history, the possibility of a metastatic neoplasm of the pancreas was considered. Fine needle aspiration cytology/core biopsy was not considered advisable in view of the risk of tumor seeding. Laparoscopic radical distal pancreatectomy was performed. The specimen comprised of the tail of the pancreas with a lobulated, glistening, myxoid pale brown to tan mass measuring 5 × 3.8 × 3 cm that extended into the peripancreatic soft tissue and was adherent to the splenic hilum. Multiple nodules were also present separate from the main mass, ranging in size from 1 to 20 mm (Fig. 2AD). On histology, a biphasic tumor with poorly differentiated anaplastic round cells punctuated by nodules of pinkish blue cartilage was noted (Fig. 3A). The cells were uniform, ovoid with hyperchromatic nuclei, and scanty cytoplasm. A pericytomatous (stag-horn) type vasculature was observed at places (Fig. 3B). The chondroid areas were juxtaposed to the round cells, and the cartilaginous component consisted of lacunae with atypical cells (Fig. 3CD). The tumor extended into the peripancreatic fat at multiple foci in the form of nodules. Lymphovascular tumor emboli were present. A diagnosis of ESMC of the pancreas was made and in view of the history, it was considered a metastasis. The immediate postoperative period was uneventful. As the margins appeared adequately excised, no further treatment was planned. The patient developed fluid collection at the operative site 5 months post-surgery. A follow-up positron emission tomography computed tomography scan 6 months post-surgery showed no evidence of recurrence. At present, the patient is alive and well (11 months post-surgery).

-

Fig. 1 Radiological imaging of the calcified pancreatic mass.

-

Fig. 2 (A, B) Intraoperative pancreatic tumor adherent to splenic hilum. (C) Distal pancreatectomy with spleen. (D) Gross image of the pancreatic mass with tan brown, glistening and myxoid surface.

-

Fig. 3 (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 40 X, dimorphic tumor with round blue cells and interspersed pink cartilage. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 400X, poorly differentiated small round blue cells with hemangiopericytomatous pattern. (C, D) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 400X, atypical hyaline cartilage with juxtaposed small blue cells.

Discussion

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma is a rare, aggressive variant of conventional chondrosarcoma constituting less than 3% of chondrosarcomas. Initially thought to arise exclusively in bone, recent literature suggests that 20 to 33% of these tumors are extraskeletal. ESMCs typically occur in young adults, in the second and third decade and have a female preponderance. These commonly occur in head and neck region including orbit, brain, meninges, lowerlimbs13,14 with rare occurrence in visceral organs such as kidney,15,16 spleen,17 and uterus.18

Metastatic tumors of the pancreas constitute less than 7% of all pancreatic masses with the common sites of the primary tumor being in the kidney and lung.11 Metastatic ESMC of the pancreas is extremely rare with only seven cases described in the literature. The primary sites of ESMC in these patients were the meninges,6 thigh,7 retroperitoneum,8 brain,9 buttock,10 chest wall,11 and femoral vein.12 Pancreatic involvement when present is usually accompanied by metastasis to other organs such as lung, lymph nodes, bone, and kidney. Our patient, in contrast, had an isolated metastasis in the pancreas. The latency period for a pancreatic metastasis from ESMC is usually between 3 and 21 years, with a rare report of synchronous presentation (Table 1).

|

Author(S) |

Year |

Age |

Sex |

Primary site |

Size of pancreatic mass |

Treatment |

Latency period for pancreatic metastasis (y) |

Metastatic site(S) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Komatsu et al6 |

1999 |

42 |

Female |

Meninges |

2.5 cm with surrounding hematoma of 5.5 cm |

Distal pancreatectomy |

17 |

Pancreas |

|

Yamamoto et al7 |

2001 |

29 |

Male |

Thigh |

– |

Distal pancreatectomy and enucleation of the head of the pancreatic tumor |

3 |

Pancreas (multiple nodules), lung, testis, skin, chest wall |

|

Naumann et al8 |

2002 |

24 |

Female |

Retroperitoneum |

– |

RT, CT |

6 |

Kidney, lung, rib, humerus, pancreas and spine |

|

Chatzipantelis et al9 |

2006 |

26 |

Male |

Brain |

3.8 cm |

Distal pancreatectomy |

9 |

Lung, thigh, pancreas |

|

Tsukamoto et al10 |

2014 |

39 |

Male |

Buttocks |

6 cm |

Surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy |

Synchronous |

Pancreas, sacrum, ilium, ischium, and lungs |

|

Smith et al11 |

2015 |

44 |

Female |

Chest wall |

– |

Distal pancreatectomy |

21 |

Pancreatic (recurrent) metastasis |

|

Guo et al12 |

2015 |

43 |

Male |

Femoral vein |

3 cm |

Distal pancreatectomy |

3 |

Pancreas, lung, pleura, mediastinal and axillary lymph nodes |

|

Present case |

2019 |

49 |

Male |

Thigh |

5 cm |

Distal pancreatectomy |

10 |

Pancreas |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; ESMC, extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma.

Patients with pancreatic metastases usually present with abdominal pain and icterus, while some remain asymptomatic and are diagnosed on routine follow-up.11 Radiologically, computed tomography shows granular irregular calcifications with surrounding hypodense tumor, while magnetic resonance imaging characteristically shows low intensity calcified areas surrounded by high-intensity tumor on T2-weighted images, suggesting a metastasis; this appearance was noted in the present case also. The past history of malignancy along with multiple pancreatic nodules on imaging raised the possibility of a metastatic pancreatic tumor in this patient.

Metastatic EMCS in the literature have ranged from 2 to 12 cm, were soft to rubbery, lobulated, and had a glistening cut surface with focal areas of hemorrhage and calcification. A similar gross appearance was encountered in the current case. Histologically, ESMCs are dimorphic tumors with undifferentiated small round cells amidst which lobules of differentiated cartilage are present. These round cells exhibit strong membranous staining for CD99, with S-100 positivity in the chondroid foci. SOX-9 is a relatively recently discovered marker that stains both the undifferentiated and the cartilaginous component in ESMC.5,19 ESMCs are usually negative for epithelial and muscle markers and hence the diagnosis on immunohistochemistry is of exclusion. In small biopsy specimens or in biopsies without chondroid areas, ancillary tests such as immunohistochemistry and cytogenetic studies play a pivotal role to exclude other small round cell tumors including Ewing’s sarcoma and synovial sarcoma. Immunohistochemical markers such as EMA, FLI-1, and CD34 are negative in ESMC, with no loss of INI-1 expression. In the present case the morphology was typical, and in view of the documented primary ESMC of the thigh, immunohistochemistry was not performed. Surgical intervention alone appears to be the preferred modality of treatment for metastatic pancreatic tumors in general, as these patients have a good survival period post-excision.11 The role of chemotherapy and radiotherapy is not clear. Our patient has had a disease-free 11 months following wide excision alone.

To conclude, metastatic ESMC of the pancreas is an extremely rare entity with only seven prior cases in the English literature. In a patient with a past history of malignancy with long latency period and characteristic radiological findings of a pancreatic mass, a metastatic process should be kept in mind. Pathological examination, including endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration cytology/biopsy, histology and/or immunohistochemistry, is the main modality to confirm the diagnosis. Radical surgery with wide excision and close follow-up may improve long-term survival and achieve palliation.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Unusual benign and malignant chondroid tumors of bone. A survey of some mesenchymal cartilage tumors and malignant chondroblastic tumors, including a few multicentric ones, as well as many atypical benign chondroblastomas and chondromyxoid fibromas. Cancer. 1959;12:1142-1157.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2002. p. :255-256. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. In: Y. Nakashima, Y.K. Park, O. Sugano, eds. Mesenchymal Chondrosarcoma. IARC Press: Lyon

- Primary extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma arising from the pancreas. Korean J Radiol. 2007;8(06):541-544.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the pancreas. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92(03):W10-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of ruptured mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the pancreas. Radiat Med. 1999;17(03):239-241.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical treatment for pancreatic metastasis from soft-tissue sarcoma: report of two cases. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24(02):198-200.

- [Google Scholar]

- Translocation der(13;21)(q10;q10) in skeletal and extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2002;15(05):572-576.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathologic features of two rare cases of mesenchymal metastatic tumors in the pancreas: review of the literature. Pancreas. 2006;33(03):301-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemotherapy improved prognosis of mesenchymal chondrosarcoma with rare metastasis to the pancreas. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2014;2014:249757.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solid tumor metastases to the pancreas diagnosed by FNA: a single-institution experience and review of the literature. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123(06):347-355.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of mesenchymal chondrosarcoma arising from the femoral vein with 8 years of follow-up. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29(07):1455.e1-1455.e5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of bone and soft tissue. A review of 111 cases. Cancer. 1986;57(12):2444-2453.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(11):1421-1424.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary renal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma: a case report. Urology. 2015;85(03):676-678.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the kidney. Int J Urol. 2006;13(03):285-286.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the spleen: report of a case. Tumori. 2011;97(04):e10-e15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sox9, a master regulator of chondrogenesis, distinguishes mesenchymal chondrosarcoma from other small blue round cell tumors. Hum Pathol. 2003;34(03):263-269.

- [Google Scholar]