Translate this page into:

Iatrogenic implantation of myxoid dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma at donor site: A case report and review of literature

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Iatrogenic implantation of chondrosarcoma (CS) is not only extremely rare but also technically avoidable and impacts with morbidity, mortality, and quality of life (QoL). We report a similar case of myxoid dedifferentiated CS at remote tissue-graft donor site (left chest-wall pectoralis major myocutaneous flap). Although the exact mechanism of primary tumor cells seeding is not clear, the probable causes are direct contamination from surgical instruments and altered blood circulation at the graft-donor site.

Keywords

Chondrosarcoma

Iatrogenic implantation

quality of life

Introduction

Iatrogenic implantation of chondrosarcoma (CS) to the remote uninvolved tissue-graft donor site is extremely rare, although incidences involving the other tumor histopathological subtypes are not uncommon in the literature. It not only poses a challenge to the repeat salvage surgery but also affects the cause-specific survival and quality of life of the patient. The most common sites involved are generally the skin and bones.1,2,3,4,5 However, the exact mechanism of seeding of the primary tumor to graft donor site is unclear and controversial. It is quite possible that such tumor seeding may happen due to poor surgical technique violating the principles of tumor surgery allowing direct transfer of viable tumor cells from the primary site to the donor site or it may result from hematogenous transfer.

The below-mentioned case report highlights regarding the very unusual appearance of CS within the surgical scar of graft donor site suggesting a possible iatrogenic tumor implantation during the reconstructive surgery.

Case Report

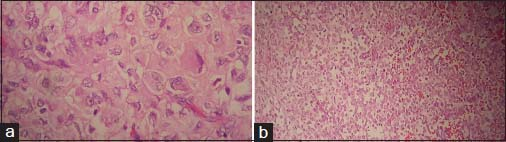

A 44-year young man, nontobacco addict and without any comorbidities, presented to our department with a painful and progressive swelling on the surgical scar site of the left chest wall for the past one month Figure 1. There were no other complaints apart from the above. Six months before, he was diagnosed with CS of the left retromolar trigone (RMT) for which he had undergone a left composite dissection (wide local excision with left hemimandibulectomy) and left-modified neck dissection with immediate reconstruction using pectoralis major myocutaneous (PMMC) flap graft harvested from the left chest in some other hospital. The postoperative histopathology and the immunohistochemistry were consistent with myxoid dedifferentiated CS Figure 2a with primary at the left RMT area. The primary tumor size was 4 cm × 3.5 cm with a depth of invasion of 1 cm with uninvolved underlying mandibular bone and free resected margins (closest margin of 1.2 cm along the posteromedial aspect of the tumor). Lymphovascular space invasion or any perineural invasion was not seen. Eight lymph nodes dissected were free of tumor. The final pathological stage was pT1 bpN0M0, Grade-III, Stage-IIA (AJCC 7th). Postoperative adjuvant radiation therapy (RT) to the tumor bed and ipsilateral neck to a dose of 50 Gy/25 fractions/35 days (from March 18, 2015, to March 23, 2015) was given.

- Swelling on the left chest wall scar (pectoralis major myocutaneous donor site). Scar of previous surgery of left neck is also seen

- (a) Sections from primary tumor show undifferentiated tumor cells with polygonal cell vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli (H and E, ×400). (b) Implantation tumor show undifferentiated tumor cells with focal chondroid matrix (H and E, ×200)

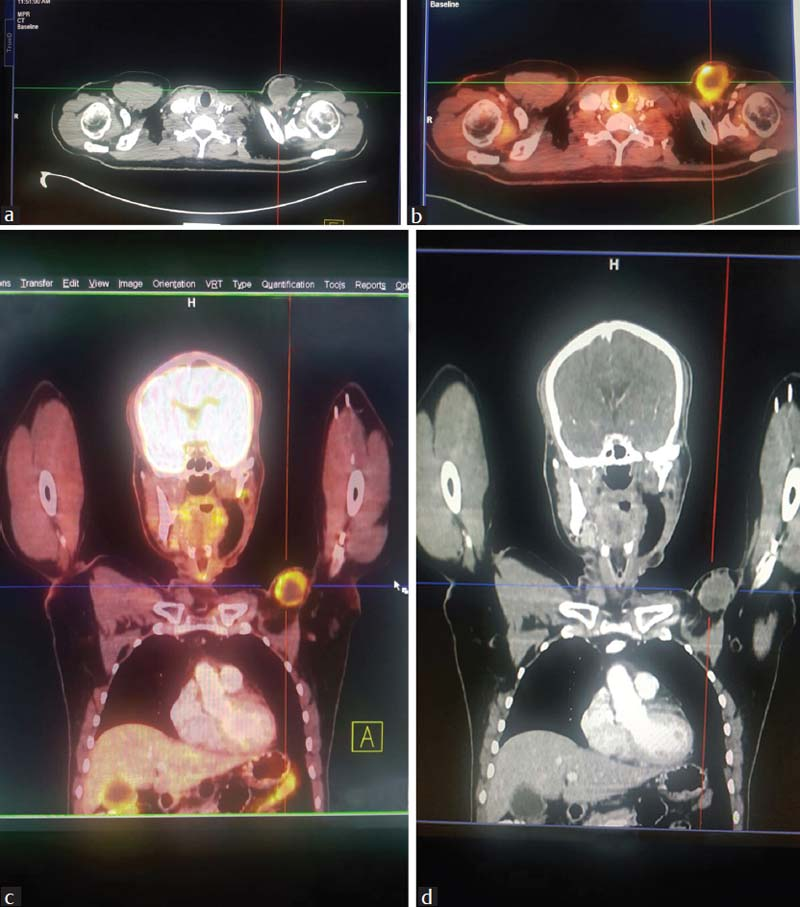

The patient presented to our center 7 months later with a solid-cystic mass on the surgical scar on the left chest wall corresponding with the PMMC flap donor site Figure 1 approximately 4 cm × 4 cm size, immobile, tender, and without any restriction of left shoulder movement or any distal neurovascular deficit at left upper limb. Rest of the primary postoperative site as well as the neck was normal. Fine-needle aspiration cytology from the above lesion was suggestive of recurrent poorly differentiated CS. Metastatic workup was done with a 18fluorodeoxy glucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography, which was showing a mass of 42 mm × 31 mm with fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose avidity (SUVmax 5) at the same anatomical site Figure 3 as on the clinical examination with no other area involvement. Subsequently, he underwent a wide local excision of the above lesion. The histopathology was myxoid dedifferentiated CS Figure 2b with negative deep margin as well as surrounding margins, closely resembling with the primary histopathology. He also received postoperative adjuvant RT to the tumor-bed with adequate margin to a dose of 60 Gy/30 fractions/43 days using 6MeV electrons prescribed at the maximum depth. He well tolerated all the treatments with good compliance and without any treatment gap. The observed maximum acute RT toxicity was Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) grade-II at the left axillary folds which were managed conservatively, and the patient recovered well.

- (a) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography thorax showing solid-cystic mass at left chest wall. (b) 18Fluorodeoxy glucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography showing fluorodeoxy glucose-avid mass at left chest wall. (c) 18Fluorodeoxy glucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography showing solid-cystic mass at left chest wall. (d) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography thorax showing solid-cystic mass at the left chest wall

Discussion

Iatrogenic implantation of the tumor cells at the graft harvest site is an avoidable complication. This not only poses a challenge to a salvageable surgical excision but also adds on to existing morbidity and even mortality in malignant tumors. Furthermore, it deeply impacts the psychological, financial, and legal implications.

CS is more common in older adults but can occur at any site of the body. Although the pelvis and chest wall are the most common sites, it is also seen in the head and neck region, consisting approximately 0.1% of the all malignant tumors of this region.6 The majority (80%–85%) are conventional CS, and the rest (15%–20%) are of clear cell, dedifferentiated, myxoid, and mesenchymal subtypes.7,8 Among the above, dedifferentiated CS not only a rare histologic variant but also rarely originates in head and neck region with a high probability of local recurrence.9 Till now, the contemporary standard of care is adequate surgical resection. However, adjuvant RT can be given in incomplete excision.10 It has also shown a high chance of recurrence as well as distant metastasis at any time ranging from a few months to several years posttreatment.11 Local recurrences are quite frequent accounting for 20%–60% of the cases. Approximately 20% of tumors metastasize predominantly to the lungs.

Our patient developed an isolated recurrence at the scar of the left PMMC donor-site within 7 months postsurgery. The chest wall or axilla has not been shown to be a site for recurrence in CS at head and neck as per the different literature survey. Hence, the above conditions hint toward an iatrogenic and neither a synchronous (simultaneous multifocal primary tumors) nor a metachronous (appearance of de novo similar lesion after removal from another site) lesion. Iatrogenic tumor implantations were first described by Ryall in 1907, believing that some recurrent tumors were due to contaminated surgical instruments with cancer cells.12 The exact mechanism of seeding of the primary tumor to graft donor site is not clear. Although direct contamination by viable tumor cells presents on gloves and surgical instruments while performing the definitive operation and harvesting autologous graft at the same sitting is most likely, however, it can be attributed to altered circulation at the healing donor site. There is some theoretical and experimental evidence that surgical trauma predisposes to the localization of tumor cells. Various theories supporting this include more circulating tumor cells with manipulation of primary tumor increased adherence of tumor cells to damaged endothelium of the microcirculation, and alteration of blood flow or coagulation mechanism in the traumatized graft harvesting site.13,14,15,16

Conclusion

Iatrogenic implantation of head and neck myxoid dedifferentiated CS at left PMMC donor site is both technically avoidable and questionable salvageability. It also deeply impacts with the morbidity, mortality, and quality of life. Adopting a proper technique of tumor surgery will potentially avoid this situation.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Risk of dissemination of cancer to flap donor sites during immediate reconstructive surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;33:573-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgery for malignant melanoma: From which limb should the graft be taken? Br J Surg. 1986;73:793-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- A pelvic osteosarcoma with metastasis to the donor site of the bone graft. A case reportInt Orthop. 1996;20:389-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic characterization of mesenchymal, clear cell, and dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:899-909. et al.

- [Google Scholar]

- Skeletal and extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: A comparative clinicopathologic, ultrastructural, and molecular study. Cancer. 1998;83:1504-21. et al.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer infection and cancer recurrences: A danger to avoid in cancer operations. Lancet. 1907;2:1311-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Possible metastasis of osteosarcoma to a remote biopsy site: A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;424:216-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of surgical trauma on experimental metastasis. Cancer. 1989;64:2035-44. et al.

- [Google Scholar]

- Susceptibility of injured tissues to hematogenous metastases: An experimental study. Ann Surg. 1964;159:933-44.

- [Google Scholar]