Translate this page into:

Pituitary carcinoma with multiple metastases: A case report and literature review

Corresponding author: Dr. Younes Dehneh, Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Center Mohammed VIth Oujda Maroc. younes.jo1@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Dehneh Y, Aldabbas M, Kada A, Elfarissi MA, Khoulali M, Oulali N, Moufid F, et al. Pituitary carcinoma with multiple metastases: A case report and literature review. Asian J Oncol. 2024;10:14. doi: 10.25259/ASJO_29_2023

Abstract

Pituitary carcinoma is traditionally defined as a tumor of adenohypophyseal cells that metastasizes systemically or craniospinally. They account for approximately 0-2% of all pituitary tumors. Their diagnosis and treatment is challenging. We report the case of a woman who was initially diagnosed with adenoma and scheduled for surgery. An MRI of the brain three weeks later showed metastatic lesions. The patient died ten days after surgery due to adrenal crisis. The development of pituitary carcinoma is extremely unusual. It could be misdiagnosed with an invasive pituitary adenoma. Until recently, treatment of pituitary carcinoma was mainly palliative and did not appear to increase overall survival.

Keywords

Pituitary carcinoma

Adenoma

Metastases

Adrenal crisis

Pituitary

INTRODUCTION

Pituitary adenomas are usually benign tumors that either remain within the sella or show expansive growth with sharply demarcated borders. Pituitary carcinomas are defined as pituitary tumors with local or systemic metastases[1] according to both the 2017 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of pituitary tumors and the 2018 European Society of Endocrinology (ESE) guidelines for aggressive pituitary tumors (APTs) and carcinomas based on the presence of metastases. Pituitary carcinomas are rare tumors, accounting for approximately 0.2–0.4% of pituitary tumors operated on.[2] Even in the absence of overt metastases, some anterior pituitary tumors exhibit almost equally aggressive behavior, responsible for increased morbidity and mortality.[3] Due to the limited therapeutic options, it is notoriously difficult to treat refractory APTs and pituitary carcinomas.

CASE REPORT

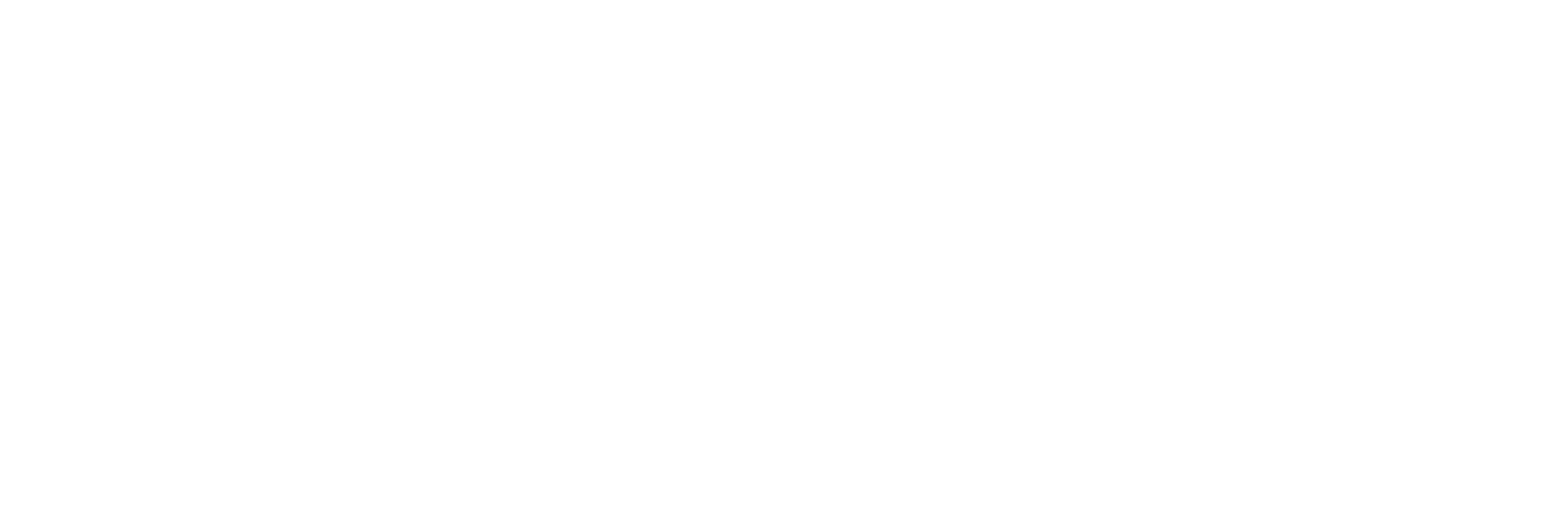

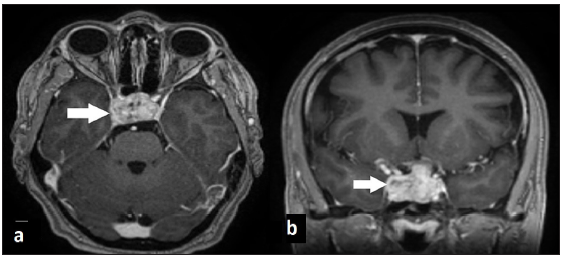

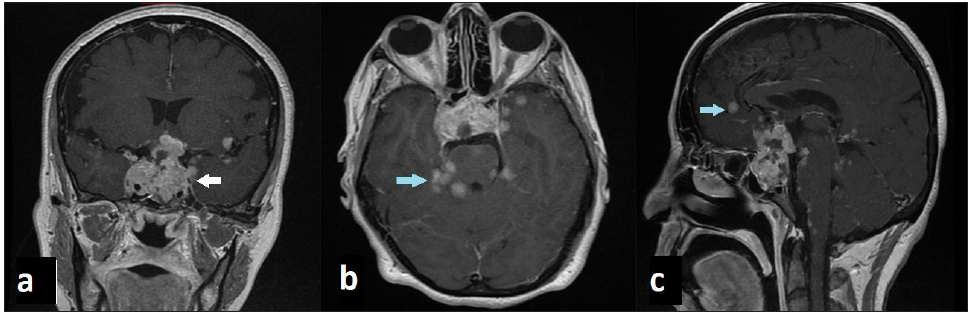

A 50-year-old female patient was scheduled for surgery for a pituitary macroadenoma discovered three weeks earlier [Figure 1], but instead, she had cholecystitis, for which surgery was reported. She was admitted to our emergency department because she had been suffering from disorders of consciousness, including disturbances in vision, for three days. Clinical examination revealed a lethargic patient with bilateral mydriasis, and ophthalmologic examination revealed that light perception was negative bilaterally. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) of the brain, as shown in Figure 2, revealed a lesion at the pituitary level with metastases in the brainstem, brain parenchyma, and leptomeningeal. A whole-body CT (computed tomography) scan revealed no other lesions. TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone) was low at 0.3 mUI/mL (0.5–5.0 mUI/mL), and she was receiving levothyroxine 50 µg per day. Plasma cortisol at 8 am (7 mcg/dL; normal range is between 5 and 25 mcg/dL), LH (luteinizing hormone) (12 mUI/mL; normal range is between 1.68 and 15 mUI/mL), FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone) (10 mUI/mL; normal range is between 1.5 and 12.4 mUI/mL), and prolactin (5 ng/mL; normal range is below 25 ng/mL)—all tests were within normal range. The patient was admitted to the operating room, where a wide excision of a mildly hemorrhagic fibrosis tumor was performed via an endoscopic endonasal approach. Anatomic pathologic examination revealed a malignant fibrosis tumor that was abundantly vascularized, with proliferation of moderately atypical medium-sized cells without visible nucleoli and significant mitotic activity. Immunostaining showed that the anti-chromogranin antibody was negative for tumor proliferation, positive for some pituitary clusters, anti-pan cytokeratin (CK) antibody (AE1/AE3), anti-CK7 antibody, and anti-octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT-4) antibody were focally positive for tumor cells, anti-endomysial antibody (anti-EMA) was diffusely positive for tumor cells, the anti-Ki-67 antibody was positive for 80% of the labeled cells, and the anti-INI-I antibody was positive for the tumor cells, neuroendocrine antibodies (anti-GH, anti LH, anti-FSH, anti-ACTH, anti-TSH, and anti-prolactin antibodies), P40, and TTF1 markers were negative, leading to a diagnosis of nonfunctioning pituitary carcinoma [Figure 3]. Postoperatively, the patient showed chills with asthenia and diabetes insipidus, plasma cortisol level was 2 mcg/dL at 8 am (normal range is between 5 and 25 mcg/dL). The adrenal crisis was diagnosed, and she received hydrocortisone (100 mg intravenous bolus) followed by 50 mg intravenously every six hours with continuous intravenous isotonic saline. The patient’s symptoms worsened. She died ten days after admission due to poor response to medical treatment.

- Brain MRI T1 weighted images with gadolinium show invasive pituitary macroadenoma (arrow) without another lesion in the brain parenchyma.

- Brain MRI in T1 weighted images with gadolinium shows pituitary carcinoma (white arrow) with brain metastases and meningeal enhancement (blue arrow).

- Microscopic images: (a) Undifferentiated tumor proliferation; (b) Anti-Ki67 antibody diffusely labeling tumor cells; (c) Anti-OCT4 antibody focal nuclear positivity of tumor cells; (d) Anti-EMA antibody x100 positive on tumor cells.

DISCUSSION

Pituitary carcinoma is a rare tumor. Most patients diagnosed with pituitary carcinoma are initially diagnosed with neuroendocrine pituitary tumors (PitNET). Early detection of pituitary carcinoma is difficult before metastatic lesions appear. They can spread to the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, leptomeninges, spinal cord, lungs, bones, and liver.[4] The route of tumor spread outside the central nervous system (CNS) is through the lymphatic and vascular spaces, whereas metastases within the CNS result from the invasion of the subarachnoid space. Hematogenous tumor spread likely occurs via the superior petrosal sinus when the cavernous sinus has been invaded by the tumor.[5] Most pituitary carcinomas present with symptoms of mass effect, including visual disturbances, diplopia, and headache, and produce hormones such as corticotropin (ACTH) and prolactin, but there are other hormone-producing tumors too. The general latency period for pituitary carcinomas ranges from a few months to 18 years.[6] It is difficult to distinguish microscopically between pituitary carcinoma and adenoma because both arise from adenohypophyseal cells, and both exhibit hypercellularity, nuclear pleomorphism, occasional mitotic figures, necrosis, and hemorrhage.[7] Several authors have advocated that the presence of metastases to distant areas of the cerebrospinal subarachnoid space is the necessary criterion for the diagnosis of pituitary carcinoma. Immunohistochemical markers such as p53 and Ki-67 have been tested to identify biomarkers associated with APTs. Tumors that have a molecular profile characteristic of an aggressive tumor (Ki-67 LI greater than 10% and p53 positivity) can be monitored more carefully.[8] High expressions of these markers can guide clinical planning, such as the decision to use adjuvant radiotherapy in cases where a pituitary tumor remains.[9] TTF1 and P40 markers are positive in lung cancer origin.[10] Treatment of pituitary carcinoma includes surgery, chemotherapy, hormone-targeting drugs, molecular therapy, and radiotherapy. Surgical removal through a transsphenoidal approach with radiotherapy is currently the treatment of choice.[11] Modern Gamma Knife radiation has shown better results compared to conventional radiation therapy; it has been shown to stop tumor growth over three years [12], and peptide receptor radiotherapy with 117Lu-DOTATATE has also been shown to be effective in controlling the growth of pituitary carcinoma over four years.[13] There are studies on several chemotherapeutic agents showing good results, such as temozolomide, by upregulating a mismatch repair protein (MSH6) and methylation of the O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase-encoding gene (MGMT).[14] Another agent is the anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) antibody bevacizumab, which suppresses tumor growth by inhibiting angiogenesis and promoting fibrosis.[15] However, the therapeutic effects of chemotherapy are controversial. The overall survival rate in patients with pituitary carcinoma is poor, but then it is worse than in patients with invasive adenomas.[11]

CONCLUSION

Pituitary carcinomas are extremely rare, where surgical resection combined with radiation and chemotherapy are necessary to help achieve tumor control. It is challenging to distinguish between invasive adenoma and pituitary carcinoma. With the broader use of molecular markers, efforts to modify the current histopathological criteria for pituitary carcinoma diagnosis may now be possible. They usually arise from invasive pituitary adenomas and are generally associated with high proliferative rates and specific gene defects, which can be used to predict the biological behavior of the tumor. Multiple treatment approaches have been established; however, treatment with all these approaches is associated with poor results. No consensus is currently established to unify the management of pituitary carcinoma. We report a rare case of pituitary carcinoma to describe our particular diagnostic.

Abbreviations

MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging

WHO: World Health Organization

ESE: European Society of Endocrinology

APT: Aggressive pituitary tumors

CT scan: Computed tomography scan

TSH: Thyroid-stimulating hormone

PitNET: Neuroendocrine pituitary tumor

CNS: Central nervous system

ACTH: Adrenocorticotropic hormone

VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor

Author contributions

All author contributed to this work.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of AI-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Pituitary carcinoma: Diagnosis and treatment. Endocrine. 2005;28:115-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An institutional experience of tumor progression to pituitary carcinoma in a 15-year cohort of 1055 consecutive pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2019;30:118-27.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical review: Diagnosis and management of pituitary carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3089-99.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intracranial and intraspinal dissemination from a growth hormone-secreting pituitary tumor. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1986;64:140-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical review: Pituitary carcinoma: Difficult diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3649-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Pathology of invasive pituitary tumors with special reference to functional classification. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:733-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pituitary carcinoma – case series and review of the literature. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biomarkers of aggressive pituitary adenomas. J Mol Endocrinol. 2012;49:R69-78.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Update on Immunohistochemistry for the diagnosis of lung cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10:72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Invasive adenoma and pituitary carcinoma: A SEER database analysis. Neurosurg Rev. 2014;37:279-85. discussion 285-6

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Pituitary carcinoma with fourth ventricle metastasis: Treatment by excision and Gamma-knife radiosurgery. Pituitary. 2014;17:514-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The use of (68)Ga DOTATATE PET/CT for diagnostic assessment and monitoring of (177)Lu DOTATATE therapy in pituitary carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:47-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The role of temozolomide in the treatment of aggressive pituitary tumors. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:923-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-VEGF therapy in pituitary carcinoma. Pituitary. 2012;15:445-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]